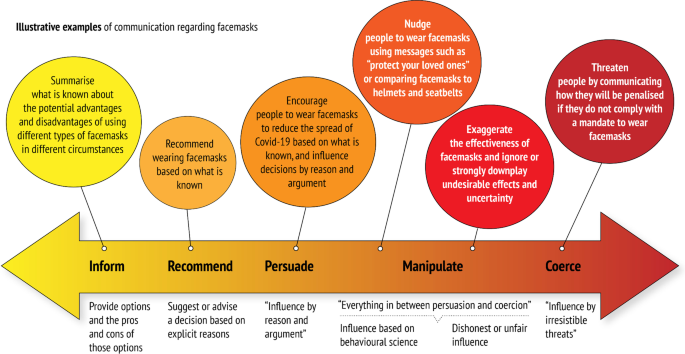

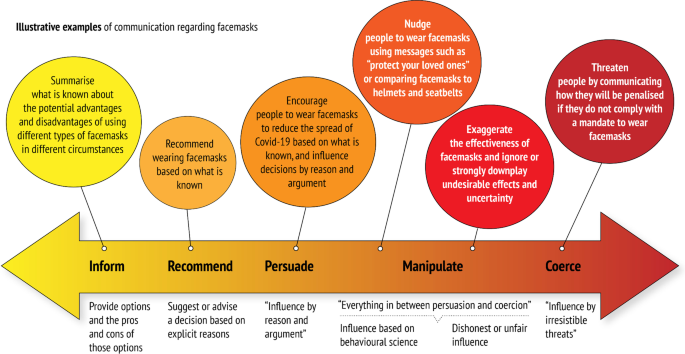

Much health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic has been designed to persuade people more than to inform them. For example, messages like “masks save lives” are intended to compel people to wear face masks, not to enable them to make an informed decision about whether to wear a face mask or to understand the justification for a mask mandate. Both persuading people and informing them are reasonable goals for health communication. However, those goals can sometimes be in conflict. In this article, we discuss potential conflicts between seeking to persuade or to inform people, the use of spin to persuade people, the ethics of persuasion, and implications for health communication in the context of the pandemic and generally. Decisions to persuade people rather than enable them to make an informed choice may be justified, but the basis for those decisions should be transparent and the evidence should not be distorted. We suggest nine principles to guide decisions by health authorities about whether to try to persuade people.

During the pandemic, governments and health authorities have recommended or mandated infection prevention and control measures, including social distancing, face masks, travel restrictions, self-isolation, quarantines, lockdowns and vaccination. Implementation of these measures has ranged from simply informing the public, to eliminating people’s ability to choose.

Public messaging about these control measures has changed as the pandemic has evolved [1]. Changes may have reflected evolving research evidence and shifting expert opinions. However, justifications have not always been shared candidly in communication by governments or health authorities to the public [2,3,4]. Additionally, researchers may have hyped the certainty and potential of their research in order to promote it [5]. As a result, the public has sometimes experienced COVID-19 messages from these authorities as untruthful and inconsistent. Thus, those messages may have exacerbated rather than reduced confusion from the tsunami of information that accompanied the pandemic.

Authorities seeking to maximize compliance may design their communication to persuade people to follow recommended or mandated control measures. However, messages designed to persuade can limit people’s ability to make informed choices and may erode public trust in authorities, which in turn can negatively impact compliance. There is evidence that public trust in government increased compliance with stringent government restrictions in both authoritarian and democratic countries [6]. Furthermore, research needed to reduce uncertainties (such as randomized trials measuring the effects of closing schools) can be difficult to conduct in an environment where those uncertainties are not acknowledged publicly.

Conversely, health authorities aiming to enable people to make informed choices (or to be transparent about the reasons for a mandate) are more likely to include what is known about the pros and cons of interventions and the reasons for recommendations or policies [7]. This approach respects the rights of individuals to be informed and enables participation in public debate. More candid communication might also make policy changes seem less arbitrary and help preserve people’s trust in health authorities [8, 9]. However, this approach could reduce compliance. For example, people may be less likely to wear face masks if they perceive them to be ineffective, and communication of uncertainty might reduce the perception of effectiveness [10]. It could also increase inequities, if some people are less likely to have access to candid information, to understand it or to be able to use it as intended [11].

Sometimes the goals of persuading and informing people are in conflict [11, 12]. This dilemma, brought into sharp contrast by the COVID-19 pandemic, exists for all types of health authorities, including public health professionals and organizations, other healthcare professionals and organizations, researchers and scientific organizations.

One way to influence people to behave in a desired way is to emphasize the advantages of the desired behaviour and ignore or downplay any disadvantages or uncertainties (Table 1). This is sometimes referred to as “spin” or “hype”. It can be done intentionally or unintentionally. Spin can be found in the scientific literature, where reporting practices distort the interpretation of results and mislead readers so that results are viewed in a more favourable light [13,14,15]. It can be found in news reports [16], advertisements used to promote the purchase of health products [17], and in public health messages [18]. Spin is manipulative when it ignores or misinforms about events or alternatives.

Information designed to inform people builds on a basic principle of respect for people’s autonomy [35]. Some autonomous choices that people make entail risks, such as riding a motorcycle. In societies that value autonomy, such choices are respected if they do not harm other people or create undue collective burden. In the context of a pandemic, many choices that people make can harm others and add to the collective burden (for example, on healthcare systems). Consequently, health authorities have frequently advocated policies that restrict autonomy and governments have implemented restrictive measures.

Information designed to influence people’s behaviour does not necessarily infringe on their autonomy, but it can if the information is manipulative [18]. Spin is manipulative if it promotes disinformation or withholds important information to direct people’s choices. For example, withholding important information about a well-documented, serious vaccine side effect that may lead people to choose not to be vaccinated or not to vaccinate their children would be manipulative, even if there is compelling evidence that the benefits far outweigh the harms. Providing information designed to arouse fear or other emotions, such as guilt or urgency, can also be manipulative. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, informing people about the gravity of the situation has been used to motivate people to adhere to control measures. People should be made aware of the seriousness of the situation so that they can make informed choices. However, exaggeration can exacerbate fear, anger and anxiety unnecessarily [36].

It can be argued that people’s choices are not truly “autonomous” when they are unknowingly shaped by their environment or by misinformation provided by actors with special interests [11], for example the food industry [37]. In addition, people do not always rationally weigh their options, and decisions are often affected by cognitive biases [38]. However, this alone does not justify manipulation of information or people’s emotions by health authorities or governments.

When authorities deliberately design information to be persuasive or “manipulative” (using behavioural science), there is an underlying assumption that they know what problems should be addressed, what preferences and goals people have, and what is best for people and the community. If these assumptions are well founded, authorities may be justified in recommending, persuading or even restricting people’s behaviour, despite some disagreement. For example, seat belt laws, traffic regulations and information to promote adherence to those are widely accepted as well founded in many countries, although not everyone agrees.

However, when there are important uncertainties or disagreements, not being honest and transparent can inhibit research and perpetuate practices that are wasteful and may be harmful. This includes uncertainty or disagreements about social, economic and other consequences not directly related to health. Moreover, one key asset for obtaining public health goals, trust, may be undermined if health authorities are not transparent or perceived to be honest by the public. Changes in policies because of changes in the evidence are likely to be more acceptable to the public if the authorities were transparent about the uncertainties of the evidence when the original policy was made.

Health information that is designed to influence people’s behaviour can also result in victim-blaming and stigmatization. For example, well-intended information campaigns to reduce obesity and the health consequences of obesity may have contributed to blaming, shaming and stigmatizing obese people [39]. Health communication about HIV and AIDS that used threats or scare tactics contributed to stigmatization [40]. The use of threats or scare tactics during the COVID-19 pandemic also may have contributed to stigmatization [36].

Not everyone wants to be informed or to make their own decisions about many of the behaviours that affect health [41]. Most people want clear, actionable messages, and for some people that is sufficient. For example, when there is a high COVID-19 infection rate, a recommendation to “wear face masks when it is not possible to maintain social distancing” is a clear actionable message. Not everyone is interested in the justification for such recommendations. Nonetheless, the justification should be reasonable, should be communicated transparently and should be available to anyone who is interested [46, 47].

It may be justified to design messages to persuade people to adhere to such recommendations. Health authorities who make decisions about what to recommend and whether to use persuasive messages should use systematic procedures informed by the best available evidence [30]. Systematic procedures should be used to decide how to communicate important recommendations, as well as for deciding what to recommend [42, 43]. Systematic procedures and transparency do not guarantee reasonable decisions any more than they guarantee that the results and interpretation of research are valid. Nonetheless, they can help to ensure accountability and reasonableness.

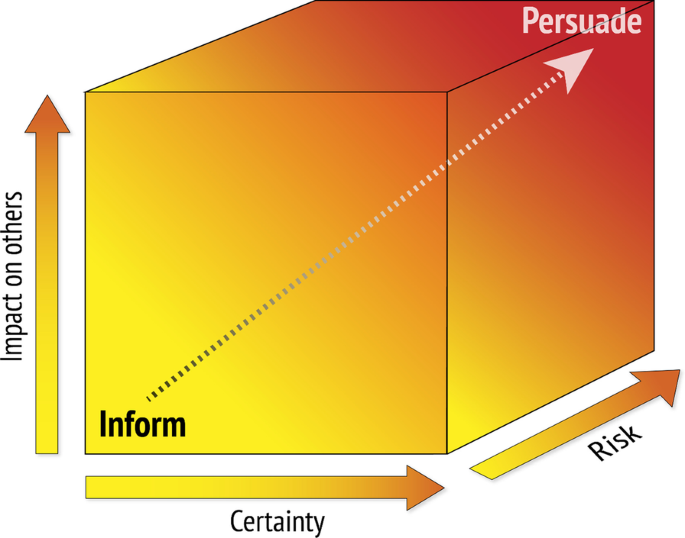

Generally, the more uncertainty there is about the balance between the advantages and disadvantages of a behaviour, the less likely it is that it is justified to try to persuade people to behave in that way (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the greater the potential impacts of a behaviour are on others (e.g. transmission of infectious diseases or drunk driving), the more likely it is that persuasion is justified [44]. Similarly, the greater the risk, the more likely it is that persuasion is justified.

Health authorities who communicate to the public in the context of health emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, must take account of ethical considerations and the extent to which persuasion is justified. The extent of uncertainty combined with the need to respond urgently may limit the ability of health authorities and governments to use systematic and transparent processes to decide what to recommend and how to communicate recommendations. However, they can be prepared for emergencies by having established systematic processes for rapidly reviewing the evidence and making recommendations and policy decisions that are informed by existing evidence [45, 46], and by implementing evidence-based guidance for communicating risk and evidence [1, 7, 47]. They also can have in place processes for generating evidence to address important uncertainties [48].

Another way in which they can be prepared is by fostering critical thinking [49, 50]. The COVID-19 pandemic has been accompanied by an “infodemic”—an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not. By fostering critical thinking skills, health authorities and governments can help to reduce people’s susceptibility to misinformation and enhance their ability to recognize and use reliable information. Currently many people lack those skills [49,50,51].

Health authorities and others responsible for communicating health information to the public should reflect carefully on the purpose of the information they communicate to the public—whether it is intended primarily to persuade people or to inform them. This should include consideration of long-term consequences as well as immediate effects on behaviour. For example, authorities who aim to persuade the public and therefore downplay uncertainty about the risk of side effects of a vaccine may increase uptake. However, if side effects are discovered over time, this could undermine trust and people’s willingness to be vaccinated in the future.

Before designing information to influence people’s behaviour in a specific direction, health authorities should be confident that the potential advantages outweigh the potential disadvantages and that most well-informed people would agree with their justification for wanting to persuade people. Deciding how to influence people parallels how to make recommendations based on evidence of variable quality [30, 52,53,54]. Generally, when there is low confidence in the evidence, strong recommendations and persuasion are not warranted. However, there are circumstances where a strong recommendation or persuasion is warranted despite important uncertainties [52,53,54]. Principles that can help guide decisions about when it is justifiable for health authorities to try to persuade people to behave in a certain way are summarized in Table 2. Answering the questions in Table 2 requires evidence, interpretation of the evidence, and judgements. Having in place an efficient system for summarizing the evidence, involving stakeholders and making transparent judgements can help to ensure that decisions and recommendations by public health authorities do more good than harm. Experience with such systems for deciding what to do or recommend can facilitate making similarly transparent judgements about how to communicate those decisions and whether to persuade people.

Both persuading people and informing them are reasonable goals for health communication. However, those goals can be in conflict. Decisions to persuade people may be justified, but the basis for those decisions should be transparent, and persuasive messages should not distort the evidence. Key messages should be upfront, using language that is appropriate for targeted audiences. In addition, it should be easy for those who are interested to dig deeper and find more detailed information, including the evidence and the justification for a recommendation or decision [7].

When there is a public health emergency, persuasion may be justified despite important uncertainties about the balance between the potential benefits and harms. However, when there are important uncertainties, they should be acknowledged. Not disclosing uncertainties distorts what is known, inhibits research to reduce important uncertainties, and can undermine public trust in health authorities. When there are important uncertainties about whether it is justified to persuade people, the impacts of persuading people should be evaluated as rigorously as possible.

We would like to thank Bjørn Morten Hofmann, Steven Woloshin, Julia Lühnen, Anke Steckelberg, Christina Lill Rolfheim-Bye, Knut Forr Børtnes and Frode Forland for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

No specific funding was received for this work. All the authors are employees of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. SL receives additional funding from the South African Medical Research Council.